What would it even mean to be a truly radical film? In 1947, social critic and philosopher Theodore Adorno offered a critique of the mass culture industry and commercial media, the relevance of which has never really faded:

“The masses, demoralized by existence under the pressure of the system and manifesting civilization only as compulsively rehearsed behavior in which rage and rebelliousness everywhere show through, are to be kept in order by the spectacle of implacable life and the exemplary conduct of those it crushes. Culture has always contributed to the subduing of revolutionary as well as of barbaric instincts. Industrial culture does something more. It inculcates the conditions on which implacable life is allowed to be lived at all...freedom to choose an ideology, which always reflects economic coercion, everywhere proves to be freedom to be the same.”

From Adorno’s infamously pessimistic, albeit justified, perspective, it is categorically fruitless to search for any serious engagement with revolutionary politics from Hollywood studios — which should surprise no one who followed their reaction to the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes last year. The immiscibility of radical politics and the culture industry is not, however, synonymous with the medium being necessarily desolate of such a perspective. Indeed, many niche film movements, from Third Cinema to Marxism-inspired Brechtian drama and Situationist film, liberated from the gilded cage of a bloated budget which produces nothing to offer audiences beyond two-and-a-half hours of watch-and-forget, are free to engage with ideas anathema to mass-market media.

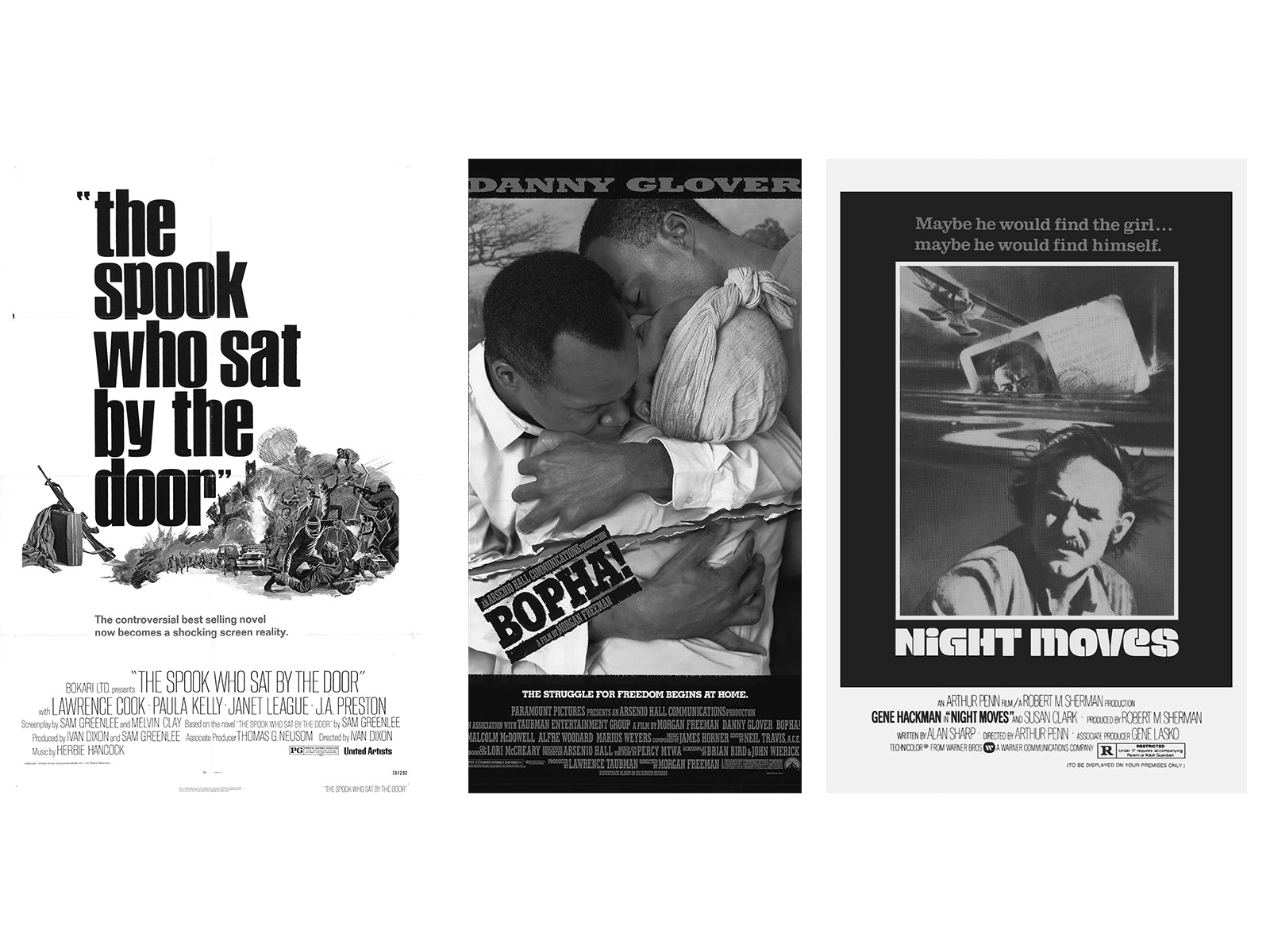

While it’s never been confessed to, The Spook (an unsubtle double entendre) has long been suspected of being the victim of being pulled from theaters by the FBI: after a handful of showings, it all but disappeared until 2004 when it was released for DVD after a mislabeled negative was rediscovered. The contents of the film makes such vigorous censorship not the slightest bit surprising. The text is filled with descriptions of the guerrilla’s tactics to the point where it reads like a training manual: blending in with and relying on the local population, hit-and-run attacks, stealing the enemy’s supplies; “In guerrilla warfare, winning is not losing.” The rarity of films which examine this subject so thoroughly in combination with its censorship has made The Spook something of a cult classic.

Yet The Spook is not without flaw. It features a welcome break from the racist caricatures which pervade Hollywood “blaxploitation” films of the ’70s and the charismatic revolutionary villain archetype espied by MacQuarrie as “the secret dictator hiding in the throat of every rebel leader, waiting to leap out and betray the non-ideological hero.” Unfortunately, this disdain of charismatic power results in characters who are two-dimensional stereotypes at best, and fails to give the (two) women more than one dimension. Indeed, while this film makes for an excellent blend of Malcolm X, Huey P. Newton, and Fred Hampton, it is conspicuously missing Angela Davis.

Nevertheless, The Spook makes for a funny, biting satire of the Civil Rights Movement and a brilliant portrayal of Black insurgency in an explosive scene-driven drama. It is a film that lays all its cards on the table without deception or twist in a synthesis of radical wish fulfillment, rhetoric, and a portrayal of race in ’70s urban America that dramatically outstrips other films of the era, making it an excellent companion to the L.A. Rebellion film movement alongside its seminal works of the 70s, such as Passing Through (1977), directed by Larry Clark, and Killer of Sheep (1978), directed by Charles Burnett. Indeed, the 1973 short film As Above, So Below, also directed by Clark, is practically a mirror image of The Spook. From head to toe, these underground gems of Black cinema embody the notion that — to borrow a twist on an apocryphal Oscar Wilde quote — everything in the world is about race, except race. Race is about economics. Without being didactic or dull, The Spook does an excellent job of setting the bar for the next forty years of film portrayal of radical characters.

This film is infused with an array of contradictions, as it must necessarily be to adequately depict apartheid — though not how one might at first guess. Despite having the highest budget of this set, it is the most obscure as measured by inflation-adjusted box office. It is the most colorful and upbeat of the three films (admittedly, a low bar) and the most viscerally violent (a much higher bar). These contradictions also extend to the narrative: the explicitly racialized economic system and society, where white South Africans compose the owning/political class, is contrasted with an almost uniformly Black workforce; and Micah’s self-centered masculine pride in his role as a police sergeant is put to shame by his son’s solemn manner, bending towards a cry for justice as Zweli’s friends and mentors are beaten, gassed, and killed.

Torture, sexual assault, chemical weapons used on students, and death behind bars ruled suicide — all elements of an unflinchingly accurate depiction of apartheid-era state violence that wouldn’t be out of place in a documentary on contemporary police brutality — pervade the narrative. White Americans unfamiliar with the nature of apartheid beyond a vague sense of racial discrimination analogous to segregation might be shocked by the level of brutality employed by the police force (and in truth, the film is generous in this regard, with each escalation enacted on the orders of superiors applying their own racist methods against the advice of the competent and dutiful local police), but not so anyone who is conscious of the history of resistance to apartheid or contemporary modes of oppression. Indeed, the past six months of horrors in Palestine should answer that question definitively. In this manner, Bopha! is an instructive commentary so often ignored in media: the ideological radical’s violence aimed towards changing the status quo is portrayed as more of an injustice than the violence required for upholding it.

The two films discussed so far are both coming-of-age stories: the latter in terms of character maturation, and the former of a nascent political consciousness. In a sense, the two perspectives are intertwined: what son does not reject his father’s politics? And as the 20th century gives way to the 21st, so too does the face of radicalism change: from hippies and punks to hacktivists, along with the modes thereof, which can be identified by the contrasts between the anti-globalization riots in Seattle (1999), Washington, D.C. (2000 and 2002), and Quebec (2001) and the protests against the Iraq War in 2003. This shift in the popular consciousness regarding radicalism among Americans is reflected neatly in the third and final film, a further two decades separated from Bopha!.

While this film depicts the more familiar strains of environmental activism as simultaneously self-congratulatory and impotent (and rightly so!), neither is it blindly uncritical of more radical tendencies — and is all the more impressive for the realism of this portrayal. Calling this a radical film is generous — the characters all operate in an idealist framework, and Reichardt has described it as “not making any political statements” — but the text delves intelligently into the cruelly ironic alienation of direct action. Josh, the main character, is an awkward, quiet, twentysomething; I picture him a year or so out of college. He is clearly driven by extreme emotion — portrayed brilliantly by Jesse Eisenberg — which he suppresses with a publicly impermeable layer of masculine inexpressiveness, putting on a facade of rational decision-making that falls apart in private under an unbearable emotional load, not unlike the film’s dam itself. As a brief aside, Josh makes me incredibly uneasy, as I see in him a character far too much like myself for comfort — which only makes the film’s deluge hit me even harder.

Reichardt has quickly become one of my favorite contemporary directors for her slow, low-budget, neo-realist style that features characters who in contrast with her apolitical protestations, by her own words, “don't have a net, who if you sneezed on them, their world would fall apart.” She is a maestra of an approach to filmmaking which the rest of Hollywood seems to eschew in favor of gaudiness; as Eric Kohn writes in Indiewire, “Reichardt’s movies are a mesmerizing statement on the solitude of everyday life for working-class people who want something better … Both sad and profoundly beautiful, her filmography evades forced exposition or histrionic confrontations.”

Naturally, all three films are period pieces, with temporal and geographic setting acting as the load-bearing framework for their respective themes. It would take as much effort to set Bopha! in modern-day America, or Night Moves in Louisiana as it would to blow up a pipeline. Despite eco-terrorism being the FBI’s “number one domestic terror threat” at the turn of the millenium making the subject a fertile one, I can’t imagine the latter being made in the decade after 9/11 or during the Clinton Administration. Frankly, I consider it remarkable that it was made as early as 2013. It does seem that the climate movement has begun to recapture some of its late 20th century radicalism in the past four years as the toll of climate change and ecocide mounts ever higher, and Night Moves, in spite of its cautionary nature, asks a pertinent question for any aspiring revolutionary that is too often disregarded among activists who dare not hope: What happens after you succeed?

In a period of cinema dominated by seemingly endless mass-market remakes, sequels, and shameless ads for merchandise, it is as a breath of fresh air to encounter transgressive art. No doubt, MacQuarrie would agree that any film which authentically depicts radical politics breaches an unspoken rule of pop culture. Too often does mainstream media make for an unsatisfying spectacle, as Jean Baudrillard identifies in his 1989 book, America:

“[T]he cinema here is not where you think it is. It is certainly not to be found in the studios the tourist crowds flock to — Universal, Paramount, etc., those subdivisions of Disneyland. If you believe that the whole of the Western world is hypostatized in America, the whole of America in California, and California in MGM and Disneyland, then this is the microcosm of the West. In fact what you are presented with in the studios is the degeneration of the cinematographic illusion, its mockery, just as what is offered in Disneyland is a parody of the world of the imagination. The sumptuous age of stars and images is reduced to a few artificial tornado effects, pathetic fake buildings, and childish tricks which the crowd pretends to be taken in by to avoid feeling too disappointed. Ghost towns, ghost people. The whole place has the same air of obsolescence about it as Sunset or Hollywood Boulevard. You come out feeling as though you have been put through some infantile simulation test. Where is the cinema? It is all around you outside, all over the city, that marvellous, continuous performance of films and scenarios. Everywhere but here.”

Indeed, Baudrillard is right in that Hollywood is but another layer in the “imperial thought machine,” and as such, we should not look for liberation in film. What then, should be the role of cinema, and art more broadly, in a political movement, and what would this form of art look like? The modernist meta-narrative of the progress of Western civilization is increasingly — and correctly — viewed as a fraud, and the irony of postmodernism has become noxious and self-defeating. A combination of modernist materialism and postmodernist non-rationalist discourse for the means in effecting change in social consciousness — which I lack the talent to create, but I consider emblemized by Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Dispossessed — might serve as a model for artists seeking to create politically meaningful long-form media. Jenny Odell’s Saving Time: Discovering a Life Beyond the Clock is also an outstanding example of this synthesis. For the dejected and cynical moviegoer, The Spook, Bopha!, and Night Moves but scratch the surface of indie and underground (and, more often than not, non-American) cinema, a rich repository of radical artistic tendencies which have spanned the past half-century and beyond ■p>