I strongly believe it will not be long before another nme is added to that list: Yunchan Lim. Two years have passed since his gold medal win in the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, the most prestigious piano competition. To mark that anniversary, I wanted to look back on Lim’s impressive career so far, and his long-lasting influence on the future of classical music.

Born in Korea, Lim began playing the piano at seven and quickly became a prodigy. He enrolled in the Korea National Institute for the Gifted in Arts at 13, and a year later won second place in his first-ever competition and third place in the Cooper International Competition as the youngest participant in its history.

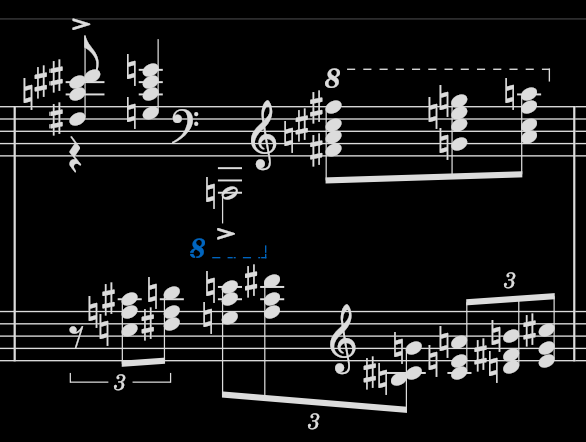

Four years later, in 2022, he was sitting onstage at Van Cliburn Concert Hall, in Fort Worth, Texas, as a finalist in the Cliburn Competition. He had already cleared the semifinals with his performance of Franz Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes. Now, in this final round, the piece before him is Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 — considered by many to be the most difficult piece for the piano given its technical complexity and physical demand.

Lim, expressionless, sits down; the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra leads him in, and he begins to play.

The concerto starts as a fairly standard rendition. But in the first six minutes, Lim takes command of the stage and transforms the piece into something else entirely. He weaves through dramatic tone shifts and delicate tempo and dynamic changes. Every single note has a weight that hangs in the air of the hall. As he plays the last parts of the piece, reality sets in: Lim was no ordinary musician.

As soon as he finishes the last triumphant chord, the audience and the orchestra erupt into thunderous applause. The conductor, Marin Alsop, wipes a tear from her eye and leans on the piano after hugging Lim. Everyone in the hall knew that what had just happened was extraordinary.

As of writing this, his performance on YouTube has 14 million views, and most if not all of the comments share the same sentiment. (If you look hard enough, you can find my comment fangirling over it.) Lim was experiencing his own Lisztomania.

He had also just made history: At 18 years old, Lim became the youngest person ever to win the Cliburn.

To say what Lim did was impressive would be an understatement; performing one of the most famously difficult pieces of all time so well, at such a young age, happens once in a generation. For me, it begs the question: What set his performance apart from the dozens of other past Cliburn winners, aside from his age?

Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 already has thousands of famous recordings, including many of the pianists I mentioned earlier. Before a performance of the piece even begins, the audience already has a preconceived notion of how it should sound. Even one of Lim’s competitors, Clayton Stephenson, had chosen to play the same concerto that night.

But Lim stood out nonetheless. Immediately after his Cliburn win, critics and fans alike were already comparing his playing to Vladimir Horowitz’s famous 1978 recording with the New York Philharmonic, regarded by many as the best rendition of the concerto.

Of course, I cannot claim that Yunchan Lim’s performance was the best; there are many others, such as those of Olga Kern and Yuja Wang, that also deserve acclaim. (For a comprehensive analysis comparing Lim to the more established recordings, I’d recommend Kris Hartley’s piece last year in The Massachusetts Review.)

But the comparisons between Horowitz and Lim are still worth exploring.